Massive Mini Team

Massive Miniteam is one of the most remarkable and up-and-coming game development studios from the regional Cologne area. Despite the studio’s young age with its foundation in 2018, its success and reputation led to its acquisition by THQ Nordic’s daughter company HandyGames three years later already. The team has a proven track record of diverse game projects including porting of ambitious indie games as well as the studio’s own ‘massive’ projects, most notably Spitlings.

One of Massive Miniteam’s Co-Founders is Michael Koloch who started out in 2014 with CGL’s Master programme Game Development & Research. Moreover, the studio has hired many more talented BA as well as MA alumni from CGL across all specializations: Lukas Fabry, Marco Cristoforetti, Olivier Haas, Trixia Quinzon, and Yasaman Farazan.

How would each of you describe the work atmosphere at Massive Miniteam? Which aspects do you value in the process of developing games?

OLIVIER (Audio Designer): It’s really employee-focused and it’s a really nice, friendly and warm atmosphere. The general mentality is that the employee’s well-being comes first – and only that will lead to a good product. That’s not necessarily the case in every company.

This also goes for how open you are. At Massive Miniteam I feel encouraged and supported when being open about struggles – in other companies this might weaken your position.

MARCO (Game Developer): I appreciate that learning process for every employee. There’s an attention to teaching your employee how to do the job instead of hiring someone who can do it already. It’s easier to shape somebody already integrated into the team instead of hiring somebody that maybe knows already everything but then doesn’t fit and does his own work that is hard to follow. I like that attention to my work, the development of a person, and how I can integrate with the team.

LUKAS (Game Developer): It’s not a typical hierarchy. Everything and the order of things we do are always open to discussion. It is determined to be a top-down hierarchy but it doesn’t feel like that. It’s also possible to make things different if you have any suggestions to do it in another way. I am working as a programmer on the current project but if I have suggestions regarding design, then the designers always have an open ear for me and for other suggestions.

YASAMAN (Game Developer): I feel that my voice is heard in the team. We have those “retros” every month where we just discuss what’s happening, what’s going well, and what’s not going well. I can always see that we are improving based on that feedback. I like this office vibe where I feel that the managers really care about how we are doing at our jobs. We are also such an international and diverse team diversifying the projects.

TRIX (Game Artist): The managers keep asking us whether we are still okay with doing our current job. In case of getting bored, we can switch to another one for now and come back later. They are always making sure that you are still enjoying what you do and not getting annoyed by anything and not having any bad emotions.

MICHAEL (Co-Founder): The reason why we founded this company is that we wanted this work environment. We worked as freelancers or at other companies before where work conditions are sometimes terrible. A really stable work environment is much more valuable than having the coolest project ever but killing yourself for it.

The atmosphere at the company is really optimistic and enthusiastic. There’s no English word for “Aufbruchstimmung” but that’s kind of what it is because we are such a young company and we grew so much – even in a pandemic and home office which is so weird. A lot of our colleagues have not seen each other in person yet. There is still a lot of growing together that has to happen so that we can feel like a team. We are a lot of really talented and effective individuals but there’s this one component that we need to cultivate but I am looking forward to that!

In May 2021, HandyGames and THQ Nordic acquired Massive Miniteam, making you a part of the Embracer Group family. In which ways did the acquisition influence your work environment?

MICHAEL: The values of Embracer Group are already aligned to a lot of our values when it comes down to health in the work environment, diversity, how employees should treat each other and more. THQ Nordic and Embracer Group are a bit different from other big gaming companies because you are not becoming a part of a bigger production. When usually being acquired by another big company, you might join them and do one tiny part of a bigger game which could be a boring or tedious task. But at Embracer Group, they are looking for indie teams. They try to help those small indie teams be as successful as they can and that success goes into the whole family. That’s how they maintain their stability. And this gave us enough stability so that we could ditch the contract work, do our own games from then on and be ourselves. Not much has changed regarding management and nothing has influenced the creative side.

What were your strategies and ideas to grow the studio before the acquisition? Which challenges did you encounter while founding and maintaining Massive Miniteam?

MICHAEL: From very early on already, we took on contract work. We wanted to be stable and the games should come eventually. So what we always said is that we are going to do 80% contract work, and 20% games, so if a game fails completely, it doesn’t really matter financially. We can just try and be slow about it and that’s fine. And it worked out. That was our first value.

Secondly, we wanted to have unlimited contracts for people. We came from backgrounds where you get limited contracts for a few months but if you want to live a proper life and maybe even have a family you cannot really go from month to month with passion only. You need to have some stability and we wanted to provide that.

“We never wanted to become one of those companies with dozens of people, all white guys. And I am so happy that we managed to get out of this hole.“

From then on, it was very hard to build a diverse team. Everyone talks about it and we also wanted to have diversity but we started with four guys. We never wanted to become one of those companies with dozens of people, all white guys. And I am so happy that we managed to get out of this hole. And we are also trying to put diverse people into a leading position because that’s the second pitfall for diversity in companies: You may have a lot of diverse people but they may all be “ground workers”. We are trying to elevate people and give them big roles, so that diversity is actually seen in the company and not like something that doesn’t change anything in the culture at all.

And the biggest challenge lately is, of course, the pandemic. We have just moved into this beautiful new office in Pulheim in January 2020, and we had to leave it in March already. That was a letdown because everything was planned and now the team is double the size. We have to rethink all the layouts and it feels like we are still moving in.

The real obstacle here was of course about the team itself. Being a real team and not only a bunch of people that work together. Everyone is efficient in home office but it is draining you. So coffee breaks, team events, and trying to cultivate a team feeling has been hard.

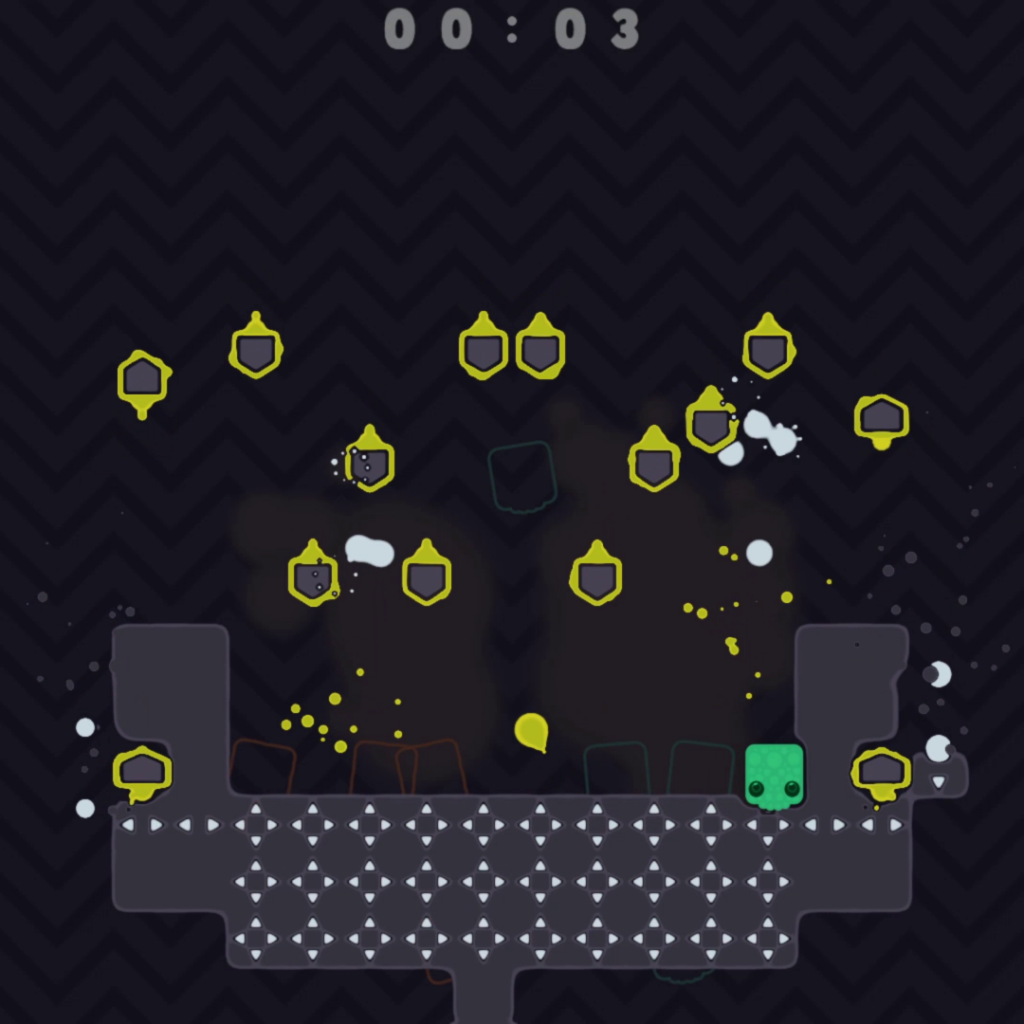

The 2D multiplayer game Spitlings was the first main title that you have developed. Which creative challenges came up during its development?

MICHAEL: Spitlings really feels like a different company because it was such a small game and we were so small making it. Back then, we were still in the Cologne Game Haus. When I think of Spitlings, I see things like Robert on the floor making the Stadia build because we already took his desk to the new office. It was so indie in contrast to what we are doing now.

One of the hardest parts in its development was giving everything context. We had the idea of the mechanics from the beginning when Spitlings was still a small side project apart from the main contract jobs that we did, but then it became a bigger and bigger project and coming up with a backstory was weird and hard for us.

Another challenge was difficulty. Until the end, we didn’t know how hard that game should be because when you are developing it, it’s so hard to judge it on your own. Designing levels in a way that they are playable with either 1 player or up to 4 players was difficult. We discussed if we wanted to have changes depending on how many players you have but then it would be four times the amount of work and we already had 200 levels plus the mutating party levels, so then we didn’t change any levels.

In the end, some of the levels ended up being really hard for our players. Some of them are super hard alone and super easy with four people, or the other way around, because sometimes with four people you have so much chaos that it would be much easier to play them alone. We actually have a handful of levels that are not finishable with four or three people because it was almost impossible to test them perfectly.

The marketing felt weird because we marketed it as a party game but it should have actually been marketed like a super hardcore platformer similar to Super Meat Boy. It was hard to tell people what the game actually is because it looked really simple, colorful and like a family party game but after a few levels the game can become too hard to play.

What was really hard is developing multiplayer itself. Before the Stadia deal, we never wanted to make it online, but in the end, online play was a good decision because co-op gameplay was a bit hard to sell during a pandemic. We had luck with that.

“If you love what you do and you are passionate about what you enjoy doing, it will reflect in your work and people will see that.”

Games like Spitlings are one of the hardest games to do online co-op for because even in other genres like shooters, you can hide a lot of synchronizations behind animations or outside of your vision. But with Spitlings, everything is on the screen, everything has a fixed position and has to look kind of right. It was super important to us to make the controls feel really good for every player. So if there’s a bit of a hiccup with your connection or you have a slow Internet connection, it looks weird. It took us so much time to work this out from the technical and design side to figure out which exact ways of synchronization feel better. There is so ridiculously much tech in this tiny game.

Regarding your single specializations of game development, what would each of you like to convey to the students of today?

TRIX: If you love what you do and you are passionate about what you enjoy doing, that will show in your work and it will reflect in your work and people will see that. Opportunities will find you and you will find people. Just enjoy what you do, be yourself and you will find a good company that fits your culture.

YASAMAN: Soft skills are really important. And I know that most developers are really introverted, I am an introvert myself, but trying to be more open and improving your soft skills really helps you in your career. You enjoy your work probably much more when you have worked on soft skills. Practices for this would be attending events like game jams, other events like conventions or other game-related or even non-game-related events. Try to do networking! Networking helped me to get to Massive Miniteam and a lot of other jobs before.

MARCO: Talking to people, getting to know people and having like an open mind to learning and doing new things got me here. So try out new stuff and learn as much as you can!

A colleague of mine told me to find your niche and you will succeed. I found my niche in porting which is a needed field, so that got me to Massive Miniteam. So find your niche and pursue it, but also the process of finding your niche means you have to try out a lot of new things. So my suggestion is: Try stuff out, find your niche, pursue it and if you don’t feel passionate about it anymore, try to find your next niche.

OLIVIER: As an audio person in the game industry it is super hard. There are only so few jobs in relation to how many want to get one. You need a lot of self-discipline and patience and it might take years.

Networking is key. Attend game jams, meetups etc. as much as you can – become someone people recognize and can relate to when reading your name or seeing your face! When thinking of my studies, the actual important part wasn’t necessarily the contents but the people I got to know and the environment I was situated in. Studying at CGL placed me in an environment full of interesting people and opportunities . However you shouldn’t be out there just with the intention of getting a job. That’s something that might happen as a side effect at some point. But first and foremost it should be about genuinely wanting to get to know people and having fun creating stuff together.

Programming skills are always recommended but you don’t need to be a pro at it. There’s only so much time and you also need to make enough room to grow in your audio-related skills. It’s rather important to know your way around a game engine and understand the basics of code, but you don’t need to do it all alone. You need to be able to think of good working audio systems and properly communicate about them – and when it comes to realizing them, work together with a programmer. It is a much more efficient approach: Combining your expertises to get the most out of it.

And as an additional note: Don’t apply for a sound design position with a composer portfolio. That’s a mistake I see being done a lot and I have done myself in the past. It’s fine when it’s a more generalistic audio position, and it’s beneficial to have composing skills, too. But if they specifically ask for a sound designer then make your portfolio all about it – show them that this is where your main skills are at and have the composing thing more like a footnote.

LUKAS: Important is, as the others already said, to attend conventions, meetups or game jams, but I would also say a solid portfolio or a collection of small projects. Make small games and complete them and not only go to an engine, click around and make one mechanic. Take this one mechanic and make a whole short game out of it, with main menu, credits, control description. Really get something done and release the game somewhere (for example on itch.io). Get people to play it and get feedback! For artists, it’s maybe more valuable to show one character of a bigger project in a portfolio, but as a programmer, it’s more valuable to have a complete build and a runnable project than just to show something which is only playable in the engine.

“Don’t try to rely on a miracle and don’t wait for your game to get finished and make you rich.”

MICHAEL: First of all, see if that process of making games is enjoyable to you. Find out if you want to play games or if you actually want to make them because making games is not playing games. I know it’s very obvious for a lot of people but some people find that out very late in their career. Game jams are a great approach to try this out.

And then what everybody else said: Finish games and release them. The releasing part is very important because this is one of the hardest parts of game development. It is important to go through the motions of producing screenshots and marketing assets for itch, putting it on there, getting feedback from players, and fixing your game even after release.

Interacting with the community is such a valuable experience.

Since I am also hiring a lot, I get a lot of emails from people who are sometimes very talented but show themselves in a very bad light. Show that you care about your own work and about the job. So take care how you write and spell-check. If you are an artist, show your art in a cool way! Don’t show me badly photographed scribbles or if you are a 3D artist, don’t show me a screenshot out of Blender without any lighting. Take care to light it nicely because this proves that you care about the project and about the product.

Regarding funding and founding a company, I can recommend finding someone that is good at finances and business. If you don’t have a background in this, get someone, preferably right into the founders’ team. And be sure that your founding team covers all the necessary bases, so have someone for programming, someone for arts, someone for design, then someone for business and finances. Then you can rely on your own skills and don’t have to hire all the skills you need to produce something.

And look for help and funding as much as you can! The Cologne area alone provides so much help with funds and seminars about business and finance. If you look for it, there are so many resources that get you started. Financially, you can get a lot of funding such as with the Film & Medienstiftung and the Mediengründerzentrum.

Don’t try to rely on a miracle and don’t wait for your game to get finished and make you rich. This only works out for a small fraction of people that you then also get to see and hear of. this is not the way to go. Founding a company is super hard and you need to put in all of your work.

www.massiveminiteam.com

www.handy-games.com/en/games/spitlings